On Art and Ignorance

|

This is a post that is based on my thinking over the past few years, and has been catalysed by a blog post from the excellent Jack of Kent, on Art and ‘Art Exhibitions’. I think he has moved into an area that is more complex than he allows. He has a degree of understanding of art history that is in at least one area greater than mine. He took an art pilgrimage (my phrase) to see a Leonardo painting in Krakow, but he would not go to London to see the same picture.

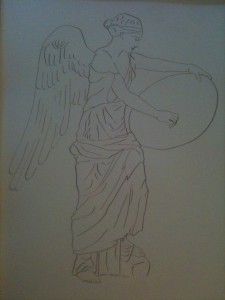

I think he overestimates people’s confidence and their knowledge. I am an artist. I did not know much about Leonardo da Vinci’s thinking. I like to read the captions in art galleries, but when the painting interests me I stop for far longer than it takes me to read the words. I examine the brushwork. I stand back and squint, looking at darks and lights. I identify tricks that have been used and wonder why others have not been. The people who have not got my training do not know how to do that. Once upon a time, everyone who looked at a picture would have been educated in what the imagery meant. (Green sleeves? Why, she’s fertile! Broken jug /and/ fallen flowers? Such scandal, my dear.) This knowledge has fallen out of favour, and hence out of the general public’s understanding. It is my thinking that a modal art-viewer comes into a gallery with little detailed knowledge. To them, the caption tells them enough about the picture that they can match it to their own world view. This can be misused, and often is. Let me tell you about my holiday… Mumble years ago, I went to a bridge convention in the South of France. I went as the fifth of four partners. In our spare time some of us looked at art. At this point, I had had no formal training at all. The people with me looked in galleries, and so did I, but I had very little money, and I knew that this was a Tourist Town. By accident I saw a sign saying ‘art show’ about a mile from the house where we were staying – it was a pleasant walk in the countryside. I did not buy anything. The next day I went back, with cash. I still have the watercolour I bought, and another smaller piece that the artist gave me after taking pity on my attempts to communicate. I bring this up because he gave me a certificate of authenticity for something I was buying in person. The thing that makes art valuable to collectors is confidence. (Will this hold its value? Is it really genuinely beautiful? Have my peers judged it?) Humans are nervous when outside their comfort zones, and galleries provide pre-vetting that says ‘this is popular’ and implies ‘it will stay so’. Personally I am in favour of the captions, but I am also in favour of the words ‘sh*t’ and ‘bull’ rearranged into a well-known phrase. I like to know what something is, but I have the ability to judge that. So, I think, does Jack of Kent. Giving people enough knowledge to look is a step short of what I would do, and a step beyond what I think he would do. Some art, frankly, is good. In a general sense the art that survives for centuries has been judged good by everyone along the way who has not destroyed it. That should be a mark in itself, but I like to know the history of a painting, and I like people to have the confidence to look at art. At the start of my current exhibition, Drawing Inspiration, (see shameless plug) I had only names and prices on the walls. I have now talked about my art for two days. My throat hurts. Tonight, I am writing out the explanations that just about everyone has asked for. (How did I make that? What gave me the idea? Is that a turnip?) I will keep an eye on people tomorrow and see if their behaviour changes, although with the artist in the room it will be very difficult to isolate reasons. So. A few things, then. Jack of Kent is right and wrong, of course. What he left out is that this is a complex situation in which people expect the captions; if you want to ignore them you may. The captions are a shortcut for a gigantic amount of lost knowledge – taking the information away does not replace what is lost. Oh, and it’s not a turnip. It might be an olive. |